Forever My StarGazer. Katana Star

Forever My StarGazer. Katana Star

Naiomi Raine our perfect angel

Naiomi Raine our perfect angel

We got pregnant immediately, but the fear lingered throughout my pregnancy, especially given everything we had been through to get to this point. Each time we went to our high-risk OB and ultrasound appointments, we were reassured that everything looked great and that Naiomi was growing well—until our 33rd week OB appointment. I mentioned to my OB that her movements had decreased (which is also noted in my office visit records), but no additional tests were run.

At my 35-week ultrasound, the sonographer told me that Naiomi was in the 52nd percentile (she had been 96% at 26 weeks and 85% at 31 weeks). My immediate reaction was, “Oh wow, she’s small, shouldn’t she be bigger?” but I was assured that this was a normal decline. I was told if the doctor saw anything concerning, they would call me. We never received that call. (I have yet to receive words of sympathy or acknowledgment of Naiomi from my MFM doctor).

A few days later, at my routine OB appointment, I was told they couldn’t find a heartbeat and that I should go across the street to the hospital. As I drove to the hospital, I knew Naiomi was gone. I couldn’t recall feeling her move that morning, and as I pressed my belly, I didn’t feel the usual response. I had to make the devastating call to my husband, asking him to come to the hospital because something was wrong with Naiomi.

We were left in a hospital room alone, with all these huge feelings, our hearts shattered and silent, mourning the loss of our daughter. As someone who has worked in healthcare and knows the importance of self-advocacy, I felt that we had done everything we could to be heard and seen. Yet, we were met with inadequate support at a time when we needed it most. I am thankful for the nurses that worked so hard to give us compassionate care while at the hosiptial recovering from my C-section, also for offering to take photos and providing the cuddle cot so that our family can spend three beautiful days with Naiomi.

Naiomi’s death has left me with an unexplainable void, an absence that no words can truly capture. But it has also fueled my commitment to advocate for families like mine who experience the devastation of pregnancy loss and stillbirth. I have come to understand that this grief is often felt in silence, particularly within Black and Brown communities, where maternal health disparities are often overlooked.

The way Naiomi’s stillbirth unfolded without enough explanation or support from my healthcare providers led me to realize how deeply flawed the system is. Black mothers, like myself, are more likely to face inadequate care, dismissal of their concerns, and ultimately, a lack of support when we experience loss. This is a story far too many of us share, and it’s one that demands change.

In Naiomi’s memory, I founded the NAIOMI Foundation to provide the care and advocacy that was so desperately needed during my own grief. Our foundation offers comfort, resources, and support to families navigating miscarriage, stillbirth, and infant loss.

Naiomi’s life, though brief, has already created ripples of change. By sharing her story, I hope to join forces with others working toward the prevention of stillbirth, ensuring that no parent feels the isolation. It is my mission to ensure that her memory lives on not only in my heart but in the work that continues to support families navigating grief.

Thank you for taking the time to hear our story. Naiomi may not have had the chance to speak for herself, but I will continue to speak for her.

We are kicking ourselves for not choosing to just deliver via c section earlier (my only living son was born via c section 4 years ago, after 12+ hours and ultimately stalled labor – couldn’t dilate past 6 cm). This most recent pregnancy seemed normal and I felt pretty good during 2nd-3rd trimester and shifted from anxieties to being more comfortable / at ease as we passed each of the milestone checkpoints with no risk indications. never would we have guessed that just a few days before I was scheduled for a c section, I felt reduced fetal movement and when we arrived at the hospital to check, the baby already had no heartbeat. later upon retrieving him, the doctors said the umbilical cord was wrapped 3 times around his body, so that was the likely cause of death, but they’re still doing a placental pathology to see if any other factors (e.g. blood clot).

how can we not feel responsible though, if we only had decided to deliver the baby earlier instead of potentially having / hoping the baby might come early on his own naturally.

as background, My first pregnancy was in early 2020 which ended in a 1st trimester miscarriage. Then came my son Yuri in April 2021, who is such a great happy kid and I know would be an amazing older brother.

We waited a little longer to try for a second kid because it took awhile to adjust to having Yuri and feeling comfortable with our little routines as a new family. But my husband and I always knew we want a bigger family long term (ideally 3-4 kids).

In November 2023 I got pregnant again with a baby girl, the whole family was rejoiced. All the early results for that pregnancy looked good, NIPT was normal etc. Then at the 20 week anatomy scan, they discovered some moderate to potentially severe congenital heart defects. We were so shocked having never been exposed to the topic before. Due to this finding, We did an amniocentesis (at the recommended of doctors) which came out normal. We also happened to be offered a free whole genome sequencing as part of a clinical trial at Columbia University, which we also agreed to because we figured maybe on the off chance that we determine a genetic cause for the heart defects, that would provide more information. Meanwhile, Upon diving into a bunch of research and getting second opinions from the top hospitals in the country for related CHDs, we decided to continue with the pregnancy knowing that there would be at least one open heart surgery in our baby’s life immediately after birth, but hopefully survivable and low risk of severe impacts to quality of life after that. Little could we predict that several weeks later on a day in early May 2024, the geneticist called me with results from the whole genome sequencing: our baby was diagnosed with ADNP which was linked to pretty severe physical and developmental delays across many parts of the heart and brain. We were devastated, and ultimately made the heartbreaking decision to terminate the pregnancy (I was already 27 weeks at the time and had to induce labor and give birth to a stillborn.) This loss felt extremely different from the first trimester miscarriage from back in 2020. It was a roller coaster of emotions going from feeling very positive about the pregnancy to then shocking news but still some hope to move forward, ultimately to have another wrench thrown that shook up and changed all earlier plans. This was also the first time both my husband and I have had to make funeral arrangements. We ended up cremating our little daughter Blueberry on 5/14/2024 and have held onto her ashes since that day.

After last year’s situation with Blueberry, we were devastated and took a couple months to really reset. But I think because of our deep desire to continue growing the family, especially during this stage while Yuri still has a chance of being closer in age with a younger sibling, we decided to try for another baby relatively soon and felt pretty lucky that physically my body and health seemed to have rebounded quite well. I got pregnant again just 3 months later (at the end of August 2024). Again, we felt so lucky but definitely had more cautious optimism in the early stages of this pregnancy. In the back of my mind, I was thinking, there are still so many milestones to pass: first trimester (everything looked normal), then we did a CVS also at 12 weeks and sent the sample for a targeted genetic test for ADNP (since we were told that given prior history, even thought this genetic condition isn’t inherited, the chances of future pregnancies having this anomaly is also 1%). We were able to rule out ADNP with this pregnancy thankfully. So then we kept proceeding slowly – the anatomy scan at 20 weeks looked normal, and the fetal echo as well.

After the 2nd trimester, I felt pretty good and getting deep into the third trimester (past 36 weeks), I basically thought we were in the clear. Everyone in our family at that point was basically waiting for me to go into labor (we all thought it might happen earlier than due date since it was a subsequent pregnancy) and nobody really suggested trying to do a c section or inducing labor earlier than due date (this is something we are curious why the doctor team didn’t suggest either). I was doing weekly BPPs and check-ins w my OB starting at week 36, so it seemed like a sufficient level of monitoring. Between weeks 36-38 they measured higher than standard levels of amniotic fluid (aka polyandrous), but the MFM docs said most of the time this is unexplained and no specific risks unless seen in conjunction with gestational diabetes and other risk factors (which I didn’t have).

When I went in for the 39 week checkup and BPP, everything still looked normal. In my nesting phase, I had so much energy that I felt very restless the last couple of weeks, so I was still taking the subway into the office every day and met up with some friends in town.

It’s only been about a week since we found out that our baby died in utero at 39 w + 4 days. I am still in shock and devastated, and also quite angry (at myself, my partner, the doctors, our family and even friends / coworkers who were around). I keep thinking, why didn’t ANY of us push for an earlier scheduled delivery so that this baby most likely would’ve been saved. And on top of that, why didn’t ANY of the medical professionals mention the non-zero risk of mortality with the baby still in utero. Although I knew in the back of my mind that there are always risks of things happening at any stage of pregnancy (including birth and even afterwards), it just feels like our baby’s death this time around was preventable. And that’s such a tough thing.

Regardless, I believe we have the strength to move forward, but right now I don’t want to. I feel lost, empty, guilty, sad and pained beyond belief that our baby boy isn’t with us anymore. That Yuri won’t get to be an older brother (for a long time at least). That I ended up having to have a c section anyway which delays and increases the risks of trying for more kids down the line. That most likely another 2+ years will pass before we even would realistically grow the family again (if ever, since I’m already 38 years old). It’s just so unfair and enraging. Why would my poor baby’s life be taken away like this?!

My pregnancy was mostly uneventful until our 20-week anatomy scan, when we learned that Baby Rogalski and I shared a two-vessel umbilical cord (instead of the typical three-vessel cord). We were referred to maternal-fetal medicine, but they reassured us that everything else looked great, so we continued my care with my midwife.

Around 34 weeks, we had another scare when I was told my amniotic fluid was low, but still within the normal range. We scheduled extra ultrasounds to monitor things, and everything remained normal. At 37 weeks, during an ultrasound, the fluid was still low-normal, so we scheduled another ultrasound for the following week, at 38 weeks.

Just a few days later, on that Thursday, I remember telling my husband, “I’m not feeling the baby move as much. Maybe we’re close to labor!” I went about my busy day working in the city. A few more days later, on Sunday, April 2, I hadn’t felt the baby move for several hours. We went to the hospital, where the receptionist assured me, “You’re probably just in labor!”, but I wasn’t prepared for what was about to happen.

We were quickly met by a kind nurse who placed nonstress test discs on my belly (at the time I didn’t know what these discs were because I had not had a NST throughout the 37+ weeks of my pregnancy). She told me she couldn’t find the heartbeat and would be getting an ultrasound machine and a doctor. I thought it was just a mistake with the machine, but when the doctor arrived, he informed us there was no heartbeat. He said a radiologist would do a second ultrasound to confirm, and then we would discuss delivery options.

The moment the doctor spoke those words, my husband’s screams were deafening, and I asked him to please stop so I could understand what was happening (like when you’re driving and need to turn down the music to focus on finding your correct next turn). It felt like hours before the radiologist came in for the second ultrasound, and it was confirmed that our beloved baby had passed away. The doctor then asked if I wanted to start the delivery process right away or go home and schedule an induction.

I was confused and asked about a c-section, but he explained that it wasn’t an option at that point. In complete shock, I turned to the nurse who had been with us and asked, “What should I do?” She suggested I go home and speak with my midwife the next day to make a plan. I’m forever grateful for her calm guidance, as I was truly unable to process what was happening.

Driving home in silence, I stared at the empty car seat we had just installed days earlier with the fullest hearts. I couldn’t believe it was real. My two best friends were also pregnant—how could I tell them? How could I tell my job that I would need to start my leave three weeks early and wouldn’t be needing the planned four months off? I thought stillbirth only happened to animals or to people in the 1800s. How could I possibly explain this to anyone when I didn’t understand it at all? This simply shouldn’t have been happening to us is all I could think at the time.

The next day, Monday, April 3, we met with my provider at 11 a.m., a later time than usual, which gave her the opportunity to speak with us for over an hour through her lunch break. We discussed options and decided that I would return to the hospital at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, April 4, for a scheduled induction.

The birth itself was surprisingly peaceful, and I’m grateful for that experience. Our angel, Baby Rogalski, was born at 7:41 a.m. the next morning. We spent 12 precious hours with him, and our closest family and friends had the chance to meet him before we said our goodbyes. I’ll never forget watching him be wheeled out of our room in a precious white cot rather than going home with us.

After speaking with other parents, I do believe we received very good care from our local hospital, although there is always room for improvement. Holding these memories isn’t easy—they weren’t the “tragic sadness” people might expect, but the moments were still incredibly hard. Our baby’s short life had a lasting impact. We talk about him every day, and now, with our living son, we embrace both the love for him and for Baby Rogalski.

Since our loss, I’ve changed careers and started working for the bereavement support non-profit that helped me get back on my feet, and I am also dedicating time to advocate for better care. I hope that in the future, routine practices like kick counting and placental measurements—things I believe could have saved Baby Rogalski—become standard for all mothers in the U.S.

When we lost our baby, we were told, “sometimes babies just die.” While that may be true for some, it wasn’t true for us. After grueling research, we were able to receive answers that Baby Rogalski died because of a small placenta, likely due to a genetic abnormality. If we had known about the small placenta while I was pregnant, we could have delivered him early and he might be here today. I will continue to advocate for changes in our healthcare system to prevent unnecessary tragedy like ours.

In loving memory of Baby Rogalski, Stillborn and still so very loved, April 5, 2023.

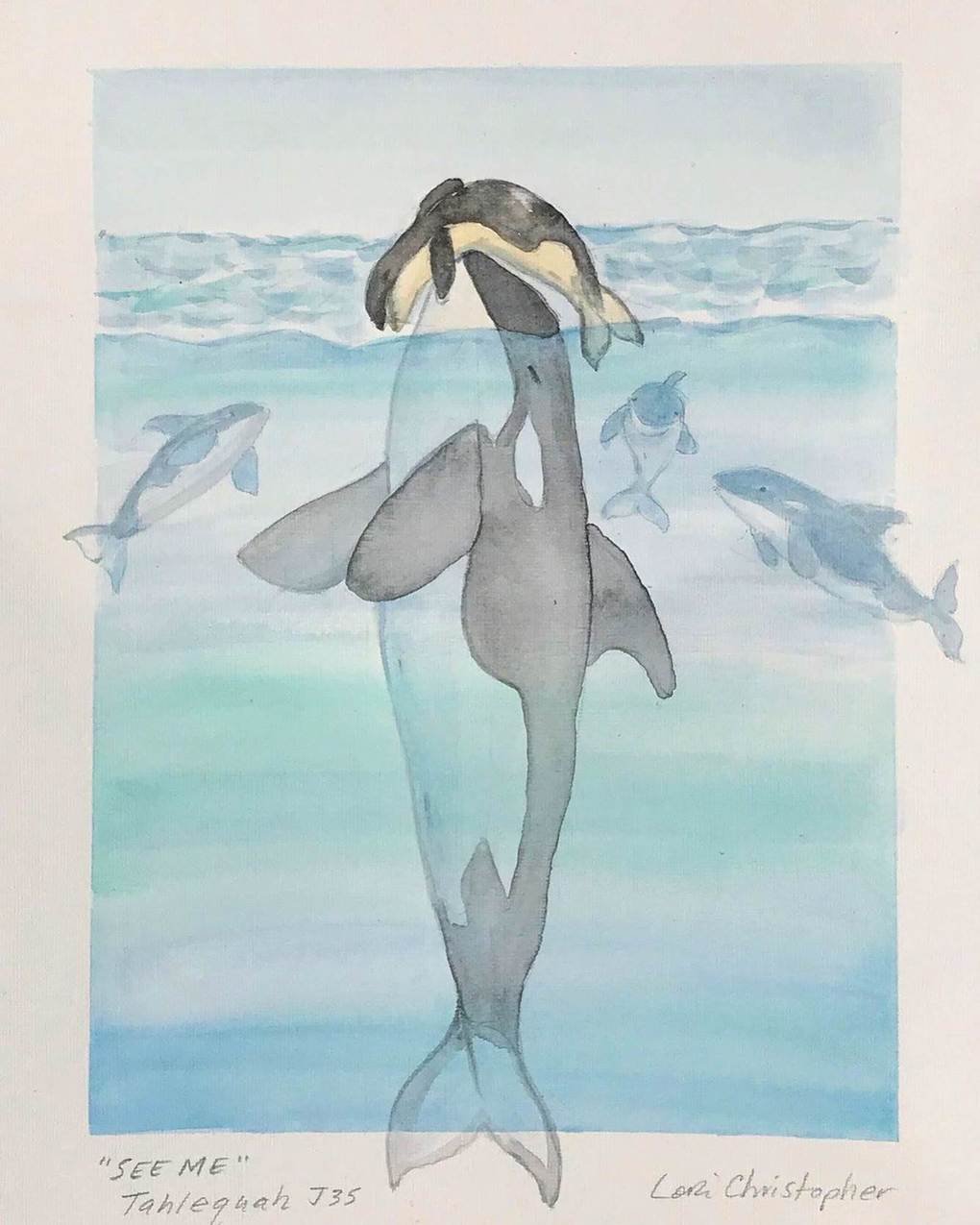

Painting by Lori Christopher

Painting by Lori Christopher

On August 25, 2005 I delivered twins- a boy and a girl. My son was stillborn, my daughter lived for 6 minutes. It was the most agonizing emotional pain I have ever gone through. The nurses had asked before I delivered them if I wanted to hold them and I initially refused. “Who does that?”, I thought. “Who holds a dead baby? Who would even want to see the baby when you know it is dead?”

I did. My husband did. Our mothers did. And, it turns out, nearly every bereaved parent I have encountered has their own story about how treasured those minutes and hours were with their stillborn baby. This story of Tahlequa, carrying her dead baby with her, having her family carry the baby when she was too tired, staying with her pod as best as she could, resonated with me- and with a lot of other bereaved parents. We would have taken 17 days if we could have.

Watching the nurse walk out with my babies, I wanted her to bring them back right away. I wanted them to be in my room- no, I wanted them to be in my bed. I wanted them to be with me while I slept, while I cried, while the world seemed to go on around us. I wanted them to be with me every minute. I wanted to undress them, to see every part of them, to imprint on my brain every millimeter of their tiny bodies. I wanted to see if they looked like me, or if they looked like my husband. I wanted to tell them what we had decided to name them, Elora and Joseph. I wanted to be a mother to them.

Tahlequa swam with her baby for a short time, and the baby died within hours of birth. I am envious that she was able to follow her maternal instincts and stay with her baby, doing what she chose to do, with no pressure to give the baby up and just keep swimming with her pod. The reports about her behavior state that carrying her dead baby kept her from eating and cost her precious energy, and I can tell you that there isn’t a mother out there who hasn’t given up eating and pushed through what little energy she had to do what was needed for her baby. Tahlequa didn’t have anyone gently explaining what might start to happen to the baby’s body if they were out of the cooling bed for too long. Tahlequa didn’t have anyone delicately preparing her for what her baby’s skin might look like after the first day, or a nurse assuring her that she could spend as much time as she would like with the baby, but she would be going on lunch and would be back in an hour, and would that be long enough for you to hold the baby? Tahlequa simply did with every bereaved mother would do, if our system and our society was able to support her though this. Tahlequa spent every moment she could with her baby.

Parents who have lost a pregnancy or whose baby has died don’t care about anything else in those early moments after their loss but to spend time with their baby. We know that this time is fleeting, and every interruption from the outside world feels like a jarring shake back into a reality where we have to begin living without our baby. Perhaps it was the lack of sleep, perhaps it was the lack of food, or perhaps it was simply blind, unconditional love for my babies that lulled me into these silent moments of just staring at them, imagining them as chubby, drooly babies in their stroller as we walked along our neighbourhood sidewalk, strangers stopping to comment on how special it was to have twins, how I must have my hands full, how their sister’s best friend had twins and then the door to my hospital room would open and a nurse would be there with a kind smile, apologizing for the interruption, but there is some paperwork to be filled out before discharge. Boom. Back I was.

Tahlequa just swam. She brought her baby with her for 17 days, 1000 miles, and then she released her baby. Bereaved parents know that moment, too. We know the moment when you walk out of the hospital, empty arms, and begin the work of living as a parent with no baby to hold. As I read alongside the rest of the world, I felt the same jarring feeling as the words spilled off of the page: “…her tour of grief is over and her behavior is remarkably frisky…the mom, seems to be doing well, very energetic…”

I couldn’t believe it. The same thing was happening to Tahlequa that happens to us after we go home from the hospital and start moving through the daily routines of life. Our society then says “She seems to be doing well, she is going back to work, I saw her take the dog for a walk, things must be okay now.” When you are fortunate to meet another parent who has shared your experience of losing a baby, the theme of these conversations all circle around what is normal, what is expected, and how impossible it feels to meet these expectations of “normal”. We compare health care experiences, we talk about our babies, we talk about the well-meaning comments of friends, family, co-workers that have cut us to the quick. “You’re still young, at least you know you can get pregnant, everything happens for a reason…”

The deafening silence that parents who have lost a baby feel when they come home and notice that no one talks about this. There are no commercials advertising where to go for help. There are no billboards telling you that you are not alone. There are no posters at the library letting you know that support is available for you.

Tahlequa, like all of us, has not completed her “tour of grief”. Grief is not limited to a number of days, or weeks, or years. Losing a baby changes who you are in the world. We may resume activities of daily living, we may return to work, we may go on to have more children. We need to have a different understanding of grief and how it looks, feels, and should be supported. We need to know that the work of a bereaved parent is learning how to incorporate the loss of their baby into their life, the work is not aimed at completing a “tour of grief”. Tahlequa’s release of her baby is not the end of her tour of grief, but rather the beginning of her learning how to be in the world as a bereaved mother.

In April 2024, I experienced dull pain around my uterus and was diagnosed with a complicated cyst that needed to be removed. I underwent surgery, and the cyst was successfully taken out.

A month after the operation, I discovered I was pregnant. I felt both happy and sad. Having just turned 40, I couldn’t believe I was pregnant again. However, the possibility of having a girl excited me.

With controlled hypertension and a diagnosis of diabetes, I was taking all the necessary medications. My pregnancy wasn’t easy, but at 20 weeks, I found out I was having a girl! Everyone around me was ecstatic, and my husband would enthusiastically say, “Finally, I’ll have a princess.” My sons would kiss my belly and greet their sister every morning. I received adorable clothing gifts, and this baby was deeply loved and anticipated.

On January 6th 2025, during my 28th week of pregnancy, I didn’t feel my baby kick, and the next day was the same. I became anxious and told my husband we needed to go to the hospital. At the nearest hospital, the doctor couldn’t detect a stable heartbeat using a Doppler, so he sent me for an ultrasound. The devastating news was that my baby had passed away.

Grief-stricken and in disbelief, I called my obstetrician, who advised me to visit the hospital the following morning, as it was already 10 pm. The next day, I was informed that I would be induced to deliver the baby. Having had all my previous births via C-section, I was terrified.

The induction lasted two agonizing days, and I finally delivered my stillborn princess. My lovely little angel was fully formed, with tiny feet, nose and lips. My little one, you will forever be in my heart.

It got me to reflect on my experience. In Uganda,where I come from, reside and gave birth to Mwezi from, what culture dictates concerning stillbirth is that associating any contact (emotional or physical ) to that baby and its loss is a taboo. Stillbirths are largely interpreted as a bad omen for marriage and usually result into forced annulments for such relationships. For others ,stillbirths are believed to be a result of witchcraft and curses so any emotional or physical contact results into repeated occurrences of the same or worse things for the bereaved families.

Therefore, many people never share these experiences at all except in confidence as a way to coach the bereaved parents on these beliefs and ensure that they too detach and reject any further connection or attachment to their stillborn baby and the entire experience.

As a result, families are forced to grieve in shame and silence, to numb their feelings and pretend they are not affected as well as end their marriages on account of the stillbirth. There are many stories of post traumatic stress disorders that they suffer sooner or later on in their lives among other terrible outcomes.

However, because of the awareness that has been happening lately, I was fortunate to have been offered the opportunity to hold my baby and bid them a proper farewell at the hospital. That I got to take some pictures with him and enjoy a few minutes of cuddling and seeing his features was what such work in this field got me.

Being that it is all I’ll ever get with Mwezi I treasure those minutes and am glad I was given a chance to spend them like that instead of wondering what my child looked like, what was wrong with me, who bewitched me etc.

It has now been 3 years since my stillbirth experience and I can confidently say that this period has had the greatest impact on my life and my surroundings so far. I have found purpose in my loss through offering peer to peer counseling and support to stillbirth bereaved families. With the help of ISA and Birth With Dignity, I have been exposed to knowledge and platforms on which I advocate for proper bereavement care, overcoming the cultural stigma around stillbirths and safer-baby care awareness which I also occasionally do in hospitals in my area of residence.

I had the most beautiful pregnancy with her, with no complications or issues. She enjoyed Indian food and listening to her dad reading books and stroking my belly, always responding with a kick or an elbow.

I went into labour at 41 weeks and I felt her last kick on the way to the hospital. We arrived and we were told there was no heartbeat. Our precious little girl had died.

Our world came crushing on us, and consequently to our families who were excited to meet the newest member. She is the first grandchild on both sides, and she stole everyone’s heart from the moment we announced I was expecting.

I want to remember her positively, and I include her in everything we do.

Leaving the hospital with a memory box instead of your baby is devastating. I will never forget the sense of void and hopelessness I had by seeing my husband walking in front of me without our precious daughter.. I always imagined him walking out with her in the baby seat.

My heart is with everyone who experienced this devastating and heartbreaking loss. I hear you and I’m walking this path alongside you

Lamentablemente no tuvimos una guía adecuada que nos dijera que era lo mejor para nosotros, por eso decidimos renunciar al cuerpo de mi bebé sin conocerlo, esperábamos vida y no teníamos conciencia de que los bebes morían. Al renunciar a su cuerpo no tuvimos derecho a nada pero yo en la UCI vi sus huellitas en un podograma (eso quedo en mi mente para siempre). En medio de mi dolor investigue y me di cuenta que no había tenido la atención adecuada por lo que luego de elaborar mi duelo decidí formarme como consultor en duelo gestacional y neonatal y hoy educo al personal de salud de mi país en este tema. Forme una asociación llamada “La maleta de Arturo” en honor a mi bebé y a través de ella asistimos a los hospitales públicos a brindar educación a los médicos en formación obstétrica, neonatal y enfermería.

Hoy La maleta de Arturo es miembro de ISA y estamos felices de poder aportar nuestros conocimientos y experiencias a esta alianza.

Vivir sin recuerdos es una tortura, nuestro taller de sensibilización lo dimos en la clínica donde Arturo nació y solicitamos el podograma, hoy tengo el podograma de mi bebé, se cuanto peso, midió y tallo. La paz llego a mi corazón con este recuerdo. Los recuerdos de nuestros bebes sanan el corazon!