Since 2017 SAWG has been posting blogs about stillbirth on Save the Children’s Healthy Newborn Network (HNN) Blog Series. So far we have contributed 31 blogs. These blogs provide an opportunity for any ISA/SAWG member to share their story. Please consider sharing yours! Click here for guidance. Click on the pictures below to read the blog.

Many fathers experience deep sorrow following stillbirth and neonatal death, an impact which is less talked about or acknowledged than the impact on mothers. One of the main findings of research that focuses on father’s experience of pregnancy loss is that men tend to be less emotionally expressive. Yet such a lack of emotion is closely linked with cultural and social expectations about what it is to be “manly”.

Some fathers have founded football teams for bereaved fathers, uncles, and grandfathers after the death of a baby. These teams provide a community of loss and one which is based on shared experiences even if the stories of how the losses occurred are slightly different.

Since 2017 SAWG has been posting blogs about stillbirth on Save the Children’s Healthy Newborn Network (HNN) Blog Series. So far we have contributed 31 blogs. These blogs provide an opportunity for any ISA/SAWG member to share their story. Please consider sharing yours! Click here for guidance. Click on the pictures below to read the blog.

As a mother and a bereaved parent, the journey of love and loss connects in ways words often fail to capture. When my precious baby was stillborn, a piece of my heart was forever changed. Yet, amidst the heartache, I discovered the importance of preserving my baby’s memory. This act of remembrance has become a tender way to honour my child, keeping her spirit alive in my daily life. Today, I want to share some of the beautiful and meaningful ways I’ve found to celebrate and cherish the memory of my angel baby Ntando, hoping they may bring comfort and solace to others walking this path. I hope that not only parents but also researchers, clinicians and policy makers will find this to be a useful resource.

I ran into a neighbor as I entered the elevator, and she unintentionally triggered a breakdown I tried my best to avoid. "Congratulations! Is it a boy or a girl?" she cheerfully asked, not realizing that I had had a stillborn baby. I was torn and conflicted by those kind words. I could only muster a soft reply, mentioning that "it" was a girl. A stark reminder of the loss I had experienced was the silent tension that overwhelmed us during the uncomfortable elevator ride. On the sixth floor, I left in a hurry because I couldn’t handle the weight of the situation.

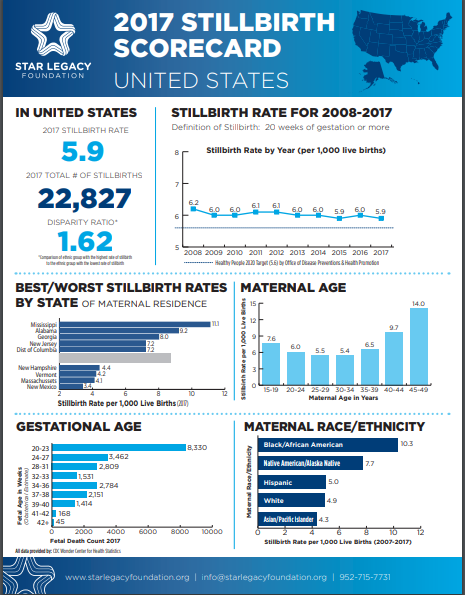

Stillbirths, pregnancy losses that happen after 20 weeks’ gestation, affect nearly 24,000 families in the United States each year. For every baby who dies of SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome), approximately 10 babies are stillborn. Despite the frequency of these tragic losses, stillbirth receives little attention, and families often feel stigmatized.

Stillbirth, the death of a baby before birth, is one of the most devastating events in obstetrics. It profoundly affects women’s and their families’ wellbeing, while the stigma associated with it makes it an unspoken sorrow in many countries. Around 2.6 million stillbirths occur each year, of which 98 percent are in low and middle-income countries, mostly due to poor living conditions and lack of good care during pregnancy and while giving birth. Stillbirth therefore is regarded as a sensitive indicator of the quality of healthcare, the living environment, and inequity in a society.

Nigeria has the second highest rate of stillbirths in the world at 42.9 per 1,000 total births as well as the second highest absolute number of stillbirths, estimated at 314,000 in 2015.[i] While the whole country faces challenges, these are particularly stark in the northern regions. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in Nigeria repeatedly show large discrepancies in access to health services between the southern and northern regions of the country.[ii] For example, the 2013 DHS reported that 55% of pregnant women in the North-West region receive no antenatal care, compared to just 4% in the South-East region. Similarly, 87.5% of women in the North-West region deliver their babies at home, while in the South-East region, 20% of deliveries occurr at home.

As the fetal movement message spreads and as pregnant women become more aware of the need to know their baby’s movements, I feel a sense of pride about the work of researchers who studied the association between fetal movement and stillbirth. Those researchers tirelessly spread the message about the issue, but I propose that we may be forgetting a core component – the “why.”

Stillbirth isn’t as uncommon as we are led to believe. Unbeknownst to many, 25,000 babies are born still every year in the United States—more than deaths resulting from SIDS and congenital anomalies combined (that is approximately 2,000 babies dying each month). Even with numbers like these, stillbirth remains one of the most understudied and underfunded public health issues today.

This past weekend I had the pleasure of attending the Consortium of Universities for Global Health annual conference, witnessing incredibly talented and enigmatic speakers share the work they are doing to ensure equitable health for all. As always, I left feeling invigorated and proud to be part of this group of individuals who are collectively offering our best effort to make sure that every baby lives, every mother lives, every individual has access to the same health opportunities that those with the highest resources enjoy. As I left the conference, the message of two speakers resonated – the first speaker argued that we need causal data associated with stillbirths. The second[i] suggested, rather controversially, that data is political.

Most of us know someone who has experienced the devastation of stillbirth. You might not be aware that you know them. You might think stillbirths only ever happen in developing countries, due to lack of healthcare quality and access. Or that they are unpreventable. Or that they are so rare that it only accounts for a negligible fraction of the global burden of disease. These misconceptions are often used to silence affected families and justify the expectations that they should just “get over it”.

Pregnant women in rural communities across Africa face enormous challenges in accessing appropriate health care. Often there are few healthcare providers available locally with the appropriate skills needed for managing complications that may arise during the pregnancy or birth.i But there are also other barriers at community level, including a lack of household funds, limited transport options to reach the health facility, lack of social support for the family or limited knowledge and awareness of danger signs in pregnancy.ii These barriers combine to result in higher rates of maternal and neonatal mortality and stillbirths among these populations and health systems are struggling to cope.

In a country like Haiti, where 60% of women deliver at home, it is not uncommon that women find themselves in very risky situations if something starts to go wrong during labor or delivery. In rural areas – the risk is even higher as villages are spread across the mountainous terrain with poor accessibility to roads or transport. In urban areas, women may not have long distances to cover but they may fear going out at night due to poor security on the roads. For poor women, finding any transport, especially at night, can be a challenge everywhere. Therefore, women may be reluctant or unable to travel to a health facility to deliver, even when they desire to do so.

In 2016, The Lancet’s Ending preventable stillbirth series presented a call to action to end preventable stillbirths by 2030. One simple action was for global partners to appropriately integrate stillbirths in women’s and children’s health initiatives, action plans, programs, publications and monitoring. A mapping of women’s and children’s health initiatives and related publications between 2011-2015, conducted for the series, demonstrated the failure to consistently and meaningfully include stillbirths in the post-2015 health agenda.

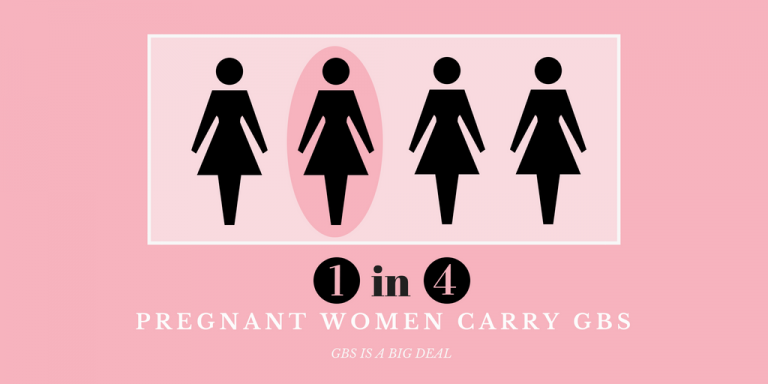

Over and over again, Group B Strep International (GBSI) hears the stories of mothers who have experienced loss caused by infections they had never heard of or that they were told were no big deal. According to one study, up to 24% of stillbirths in developed countries have been attributable to infection. Another study suggests that infection contributes to nearly half of the stillbirths in developing countries.

The voice of the stillborn is too silent to be heard. Ghana is committed to improving the health of pregnant women and newborns. There are a lot of social pro-poor interventions going on in Ghana to ensure that pregnant women have access to skilled care during pregnancy and delivery. Under the National Health Insurance Scheme, pregnant women can access services including antenatal care and delivery and the babies have access to free care for the first three months linked to their mothers after which period the child is registered as an individual.

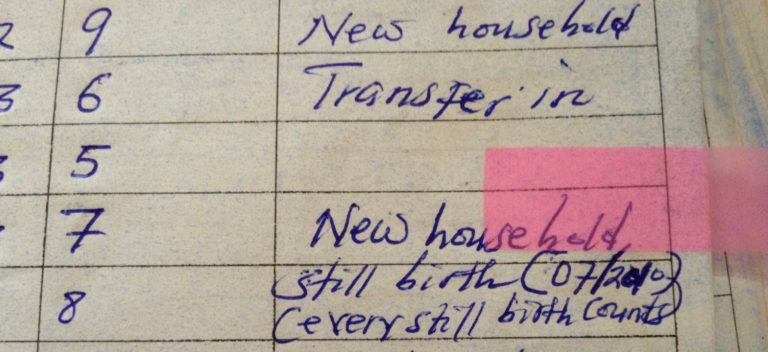

Every Newborn Action Plan 2014, called for “Counting Every Newborn” by investing in birth and death registration coverage and quality, promoting recording of every birth, live or stillbirth, and recording stillbirths and neonatal deaths and institutionalizing perinatal death reviews and taking action to address avoidable factors identified through these reviews.

As a bereaved parent and stillbirth researcher, I believe that the motivation for change comes from a lived experience. It devastates me that stillbirth is still occurring time and time again. There is a constant feeling of being unheard, our experiences and babies never acknowledged by our communities and governments. We know that when a government acts to reduce stillbirths and listen to bereaved families, however, change can occur; Scotland, Norway, the Netherlands and New Zealand are notable examples. In Scotland, for instance, the Maternity and Children Quality Improvement Collaborative (MCQIC) introduced a requirement that all health care providers have a documented discussion with pregnant women about the importance of fetal movements and their connection to stillbirth.

The placenta is a vital organ that develops during pregnancy to support the growth of the developing baby. Sometimes the placenta doesn’t work as well as it should. The placenta may struggle to deliver all the oxygen and nutrients necessary to support the growing fetus. When its measurements are compared to other developing fetuses of the same age, a baby growing inside a mother with reduced placental function is smaller than its peers (called a fetal growth restriction or intrauterine growth restriction IUGR.) These babies are more likely to be stillborn, be born preterm, and face health complications after birth. (Gardosi, 2013).

While teaching nursing students in Uganda for many years, I, along with my friend and colleague, Lynn Zdechlik, witnessed many maternal and perinatal deaths. As nursing professors, and midwives, we felt burdened to educate nursing, midwifery, and medical students on high-risk perinatal care. Kiguli states in her article for Lancet that “Uganda ranks 10th in the world for stillbirth and strategies are needed to address preventable stillbirths as well as follow up with supportive services. (Kiguli, J et al., 2016)

It was a warm summer’s day in Stockholm, July 2013. We were expecting our first baby and naming him August. We had celebrated Swedish Midsummer and were now just waiting for his arrival. One day in week 41 of my pregnancy, I felt something was different. I had not felt August kick and neither had I felt him move in me. Hours later, a midwife told me that my baby no longer had a heartbeat. I did not understand what she had said. What did she try to tell me?

The significance of stillbirth around the world has been documented. Unfortunately, awareness of the issue in our society and commitment by organizations and health systems to addressing it has been scarce. While the majority of the world’s stillbirths occur in low-resource settings, the numbers in high-resource countries are not insignificant.

I got married on December 12, 2003, and after two month of marriage I conceived my firstborn. The ultrasound scan revealed a male fetus and this was good news for us. We were all excited. We developed a serious attachment to him, to the extent that I had taught my husband (a professional accountant) to listen to the fetal heartbeat. He listened to it every morning before he left for work and every evening upon his return, greeting the baby and welcoming him to our family. The baby would respond by moving within my womb.

The rapid onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has thrust the importance of care around death and the dying to the front of our collective global consciousness. Daily media reports have highlighted not only the statistics and science behind the pandemic, but more importantly, the moving, real-life stories of those individuals who have died, often in isolation, as a result of the deadly virus.

Pregnancy loss and neonatal death are devastating realities experienced by millions of families worldwide each year. However, along with loss and grief more broadly, pregnancy and infant loss have, historically, been seldom discussed. As a consequence, bereaved parents have reported experiences of stigma, shame and disenfranchisement. In addition, what attention there has been on grief following pregnancy loss and neonatal death, has typically focused on women.

Over the past two decades, substantial progress has been made in reducing the stillbirth rate around the world. However, in some regions, population growth is outpacing the decrease in stillbirth rates. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of two regions where that is happening – and its portion of the global number of stillbirths has increased from 27% in 2000 to 42% in 2019(i).

On January 7, 2021, I published an opinion piece about why we need to take action to reduce preventable stillbirths in Canada. In it, I explain how my daughter was stillborn in 2012 and how she could have been saved had I known about the importance of fetal movement monitoring in the third trimester of pregnancy. In it, I encouraged readers to sign a petition I initiated in October 2020 asking the Government of Canada to take action to reduce the Canadian stillbirth rate by following the lead of countries such as Australia and the UK, both of which have national action plans to reduce stillbirth that include recommendations for fetal movement monitoring. Stillbirth is a public health issue that is neglected, invisible and absent in current Canadian public policies despite more than 3,000 babies who are stillborn every year. My petition was meant to be a wake-up call for the government and the first step in a broader attempt to effect change in Canada.

A 26-year-old woman arrived at an urban health center in Mali, West Africa, 40 weeks pregnant. A medical officer had referred her to the center for failure to progress in labor. She attended four prenatal care visits with normal findings and completed all recommended prophylaxis. Upon examination, one of the authors, Dr. Soumaré, could not hear a fetal heartbeat and found meconium-stained amniotic fluid. The young woman’s first full-term pregnancy ended with delivery of her stillborn son.